Cultivating Legacies: An Interview with enBloom (Part 1)

TW: discussions of enslavement, systemic racism, and white supremacist practices

Over the course of the 20th century, the Black diaspora in the United States lost over 90% of the approximate 16 million acres of land they accumulated after the end of enslavement. For generations following the Civil War, freedpeople purchased as much land as they could afford wherever they could. Many of them also worked the same land for decades, investing more in their blood, sweat, and tears than any amount of money could match.

Their progress was unraveled by white supremacist practices built into American systems and extrajudicial (but often legally condoned) racial violence. Land was stolen from Black farmers through Jim Crow culture, sharecropping, financial discrimination, voter suppression, eminent domain, and other forms of systemic racism.

This land theft destroyed centers of African American culture and community, and prevented Black communities across the U.S. from developing intergenerational wealth. We see its legacy in socioeconomic outcomes like food apartheid and lack of safe, affordable housing disproportionately impacting BIPOC communities.

Joi Howard and Michael Ligons, co-founders of the nonprofit enBloom, are acutely aware of this history and its continuing legacy. They also use it to drive enBloom in the work they do every day: building sustainable communities through holistic wellness initiatives.

Joi and Michael founded enBloom in 2021 along with Kieron George, a business owner and activist in Baltimore. Together, they began building a collective that would create a brighter future, investing in youth through their community garden program at schools in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Their programs also include a grower’s market and a women’s circle, each led by different members of the enBloom team.

And after a century a decreasing Black land ownership, Joi, Michael, and the other leaders of enBloom are doing their part to reverse this trend through local land ownership.

There is no way to return all of the land that was stolen to every person stolen from – none of this even touches on the fact that the land being debated over was not and is not even the U.S.’ to buy or sell, as this land had been inhabited for thousands of years prior by hundreds of different Indigenous tribes, many of which continue to exist today.

However, through the work of organizations like enBloom, we can repair some of the harm by making sure their descendants have the foundation they deserve (and reparations from the government, but that’s another post).

enBloom’s mission emulates a lot of our values, particularly their belief in the immense power of community. We’re really excited to see how their programming grows from here and collaborating more with them in advocacy around Crownsville Hospital (which you’ll hear more about in Part 2!).

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Emma Buchman, she/her (Editor, The Magpie):

Thank you both so much for agreeing to sit down with me to talk about enBloom. I love your mission and the vision that you have for our communities and in wellness and sustainability. I’m gonna ask a few questions and whoever has an answer first can answer, but you’re both welcome to answer every question. First, could you each tell me a little bit about yourself? Who are you and what do you do?

Michael Ligons, he/him (Co-founder, enBloom):

…For the past 20 years, professionally, my background is finance and accounting. I’ve worked with some large banks in New York, and now I’m currently here in Baltimore.

My passions in life really evolve around a lot of things outdoors. So, in addition to the financial markets and stock trading, things that I do

professionally, I also like to kayak, mountain bike, go camping, hiking, whitewater rafting, snowboarding. Anything outdoors.

I’ve been working with Joi on this initiative for the past three years. Truly, it has been a defining moment in my life. I think this is one of the things that I would call a legacy movement, if you will; fast forward to my grandkids, my great-grandkids, and they look back and they ask themselves, “What did we know about PopPop?” It would be that PopPop built gardens all throughout the state, all throughout the country, all over the world, and really tried to make food accessible to all. That’s what I have.

Joi Howard, she/they (Co-founder, enBloom):

I like you using that word “legacy”, because it definitely feels like a long journey. It is not a sprint by any means… It’s hard. It’s a lot of work. <laugh>.

Joi Howard, I’m one of the founding members of the enBloom collective. My background is in operations, project management, and event management. I have a twin brother. My brother and I were born in Atlanta, but my parents are from Baltimore City and we moved back to Maryland when I was eight.

I’ve always been connected to nature and the environment, but growing up, it just never felt like a real viable career path. It just felt like something that was nice to be around… I did go to the Western School of Technology and Environmental Science in Catonsville. I was in one of the first classes at that school. But even still, it just didn’t feel like a true career path.

I went to work for different universities, primarily doing events and alumni relations. I love that now I have found myself using the skills that I attained professionally, but back in this agrarian space to reconnect Black people to agriculture and to create autonomy and healing and wellness. And it not just be the Old McDonald, growing tomatoes to see if we can do it… but to take it a step beyond that and really use it as an opportunity to create jobs, to generate generational wealth and wellness within our community.

I feel called to this space. It came about at a time when I was having challenges in my life, and really wanted to address it in a holistic way and be a good example for my daughters. At the same time I came across Crownsville. So all the stars aligned for me to be positioned to do this work today… I’ll stop there. <laugh>

Joi Howard & Michael Ligons, two of enBloom’s co-founders.

Emma:

…So, I wanted to talk about enBloom. First off, what is enBloom? What is it that you guys do, and what’s your primary mission?

Joi:

We use the acronym, “With enBloom, everyone EATS.” So ‘E’ stands for exposure, ‘A’ is for access, ‘T’ is for training, and ‘S’ is for sustainability.

In relation to both agriculture and wellness, it’s about access to alternative modalities of healing and wellness, like yoga, acupuncture, reiki… A lot of people know about prescription medication or street drugs or alcohol, but may not have had exposure to some of the alternatives.

We have two main programs right now: Communities enBloom, which focuses on that exposure and access to wellness. Then Schools enBloom was the second arm; [it was] us piloting, on a small scale, what this agricultural-based education or work experience could be. You’re growing food, but then also harvesting it, processing it, collecting data, and being exposed to different jobs around taking food from produce to value-add, and creating a product to sell and generate revenue for and by the people within the communities where the food was grown… I don’t know if you wanna add anything to that, Mike?

Michael:

I think that was great and very comprehensive. The other thing that we really, really want to implement is that economic component.

We understand the world in which we live. This is a capitalistic society. We not only want to show people, empower them, to pick a new skill set; but [how to] leverage the skill set and make a significant living for you and your family. These don’t have to be side hustles.

We really want to build a paradigm where people run multinational corporations based on health and providing alternative ways to cure diseases… and not just thinking small scale, we can actually scale this up. Scale is important.

Emma:

…Why did you decide to make agriculture and sustainability core components of enBloom’s vision?

Joi:

I’m glad you asked that question…There’s one more founding member, Kieron George – we came together. All of us had a love for nature and agriculture, we’re all around the same age. Agriculture in the Black community, it’s increasingly becoming more popular. It hasn’t been “sexy” in the Black community for a long time, for obvious reasons.

But it’s healing. There’s so much that you can learn from it. Food is medicine.

We’re reclaiming that narrative. It’s not all about slavery and toil and struggle; it’s also an opportunity for us to heal from transgenerational trauma and be a tool for uplifting the community.

For the sustainability piece of it, a big part of the model is being collectively owned and operating. The decisions are made like a cooperative, is the word that most people are becoming more familiar with, is growing in popularity, where it’s collectively owned and operating, and decisions are made by the people that are most impacted by it. The community land trust is an opportunity for collective ownership of land.

You know, Black land loss is real, especially in Anne Arundel County. It can be said for lots of places in the US and abroad that to acquire land is difficult, and it is expensive. The collective or the cooperative, plus the community land trust is a way for people to start to generate wealth and have autonomy within their own households and communities.

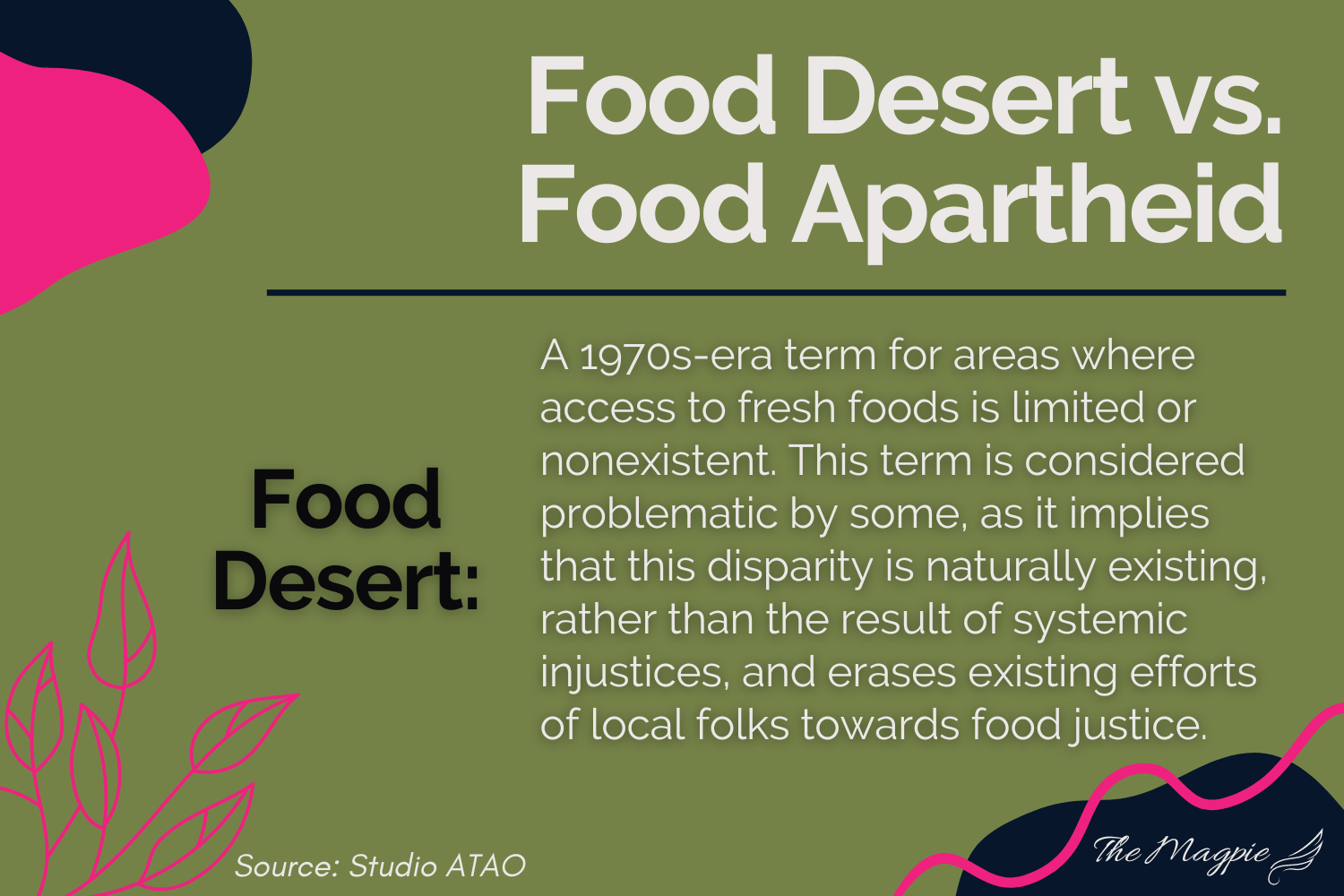

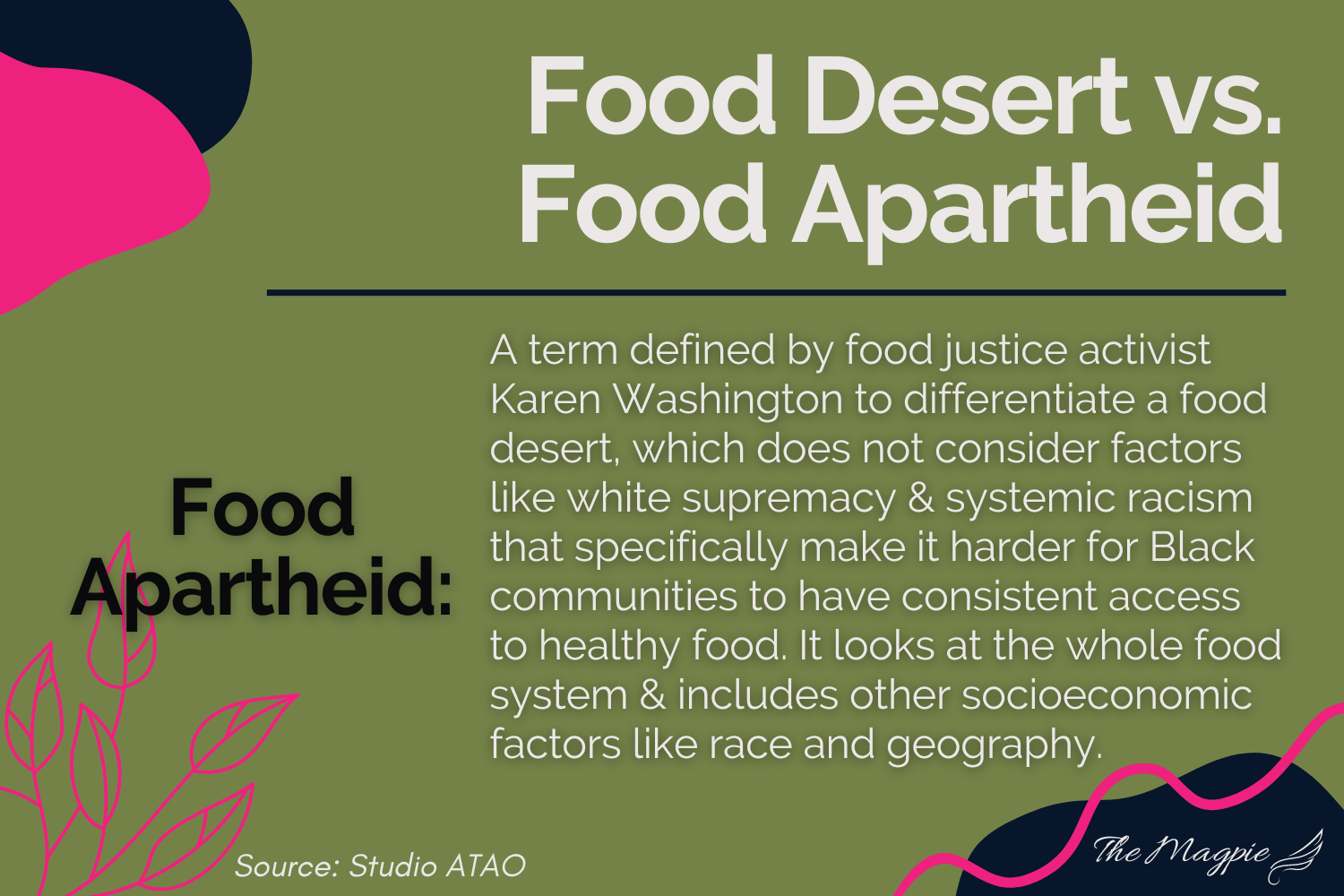

A few definitions from specialized topics we discuss in this piece!

Michael:

Great answer. If I could just take a stab at that same question, why agriculture and sustainability – people’s decisions on what they choose to put in their body on a daily basis is probably the most important thing that we do, that a lot of us are uneducated around and don’t necessarily always have the best options available, right? Going back to empowering people, how to make informed decisions on their body, and then giving them the resources so they can actually do it.

It’s one thing to say, “Okay, you should eat five fruits and vegetables a day.” I agree with you wholeheartedly; but I live in the middle of a desert in Baltimore City. That information is not real to me, so you can actually solve the problem of getting food to me. That part of agriculture, I’m so passionate about, because if you don’t give them the actual orange to eat, or the banana, or the kale, or spinach, all the education in the world means not.

Then the second thing about sustainability – when I hear “sustainability”, I hear “stewardship”. In my last response I was talking about multinational corporations: we’ve seen what corporations have done in the world. We’ve seen the oceans of plastic, what it has done to the environment, the oil spills… Corporate responsibility is not something that we’ve actually taken seriously as a society, and we’re starting to feel the impacts of what that has been over generations.

So when we at enBloom think about sustainability, it’s that component of being a good steward and being responsible of what it is that you’re doing in the world, and knowing that whatever it is that you built is gonna affect your children and your grandchildren and great- great-grandchildren. Be mindful of the environment that you want to create for them, but consider that it starts today.

Emma:

Amazing. Thank you. Staying in line with what your vision and mission are, how would enBloom define “wellness”? What would be a “well” person, a well community?

Joi:

<laugh>. You’re asking all the questions that come up a lot! As we have been speaking to hundreds of people over these past few years, they say, “Wow, Joi, this is big. This is a lot. There’s so many components to it”, and it’s because there are seven areas of wellness that we want to address.

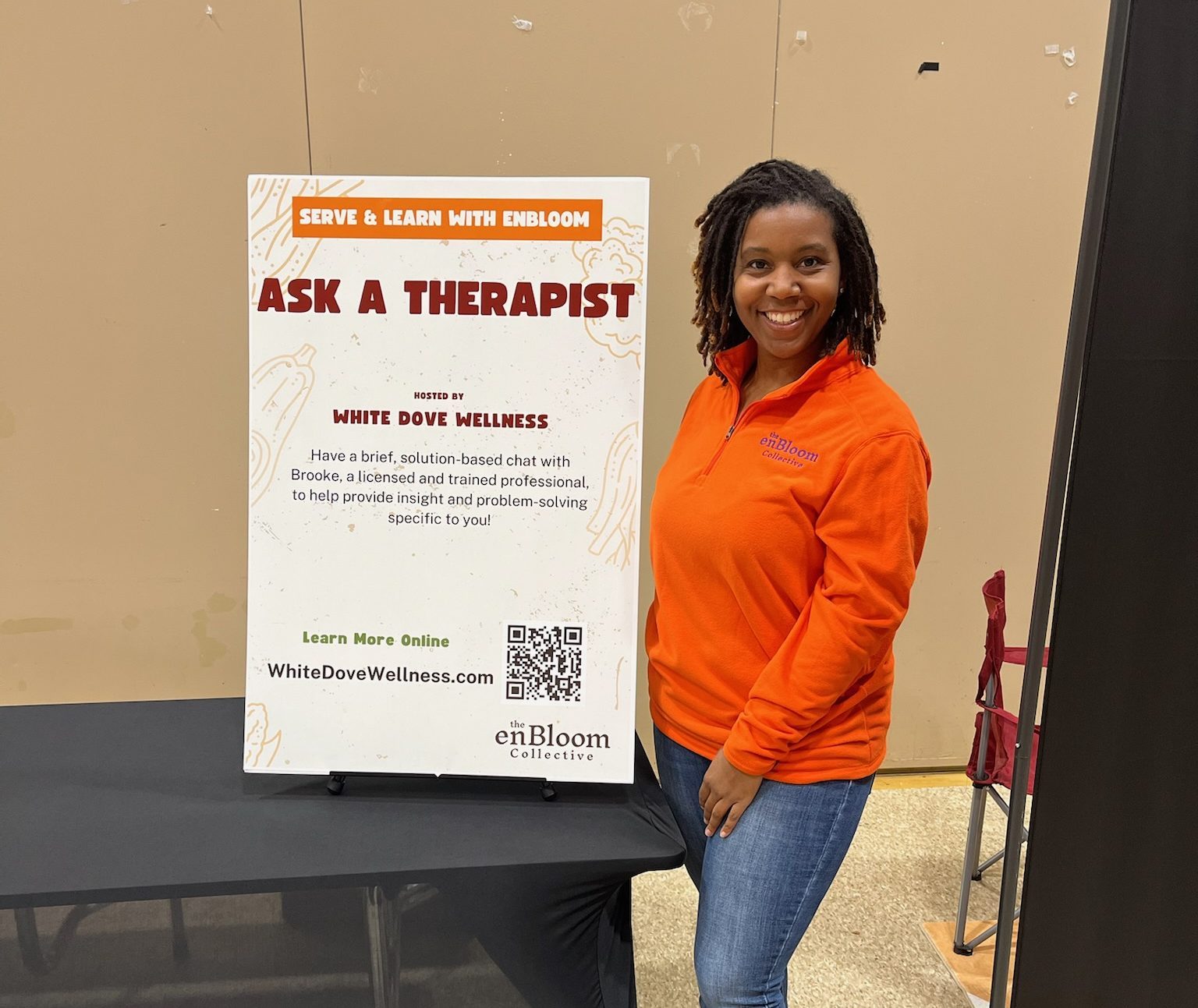

To be a fully whole person we have to take into consideration our environmental, social, mental, physical, occupational, economic, and creative health.

We tend to pour into a few of those buckets, the way that our society is built. But we can’t operate at a deficit for very long, in any of those areas. So addressing all of those areas holistically is what we’re focused on. That’s why we have the alternative wellness.

But it’s also creating job opportunities or the possibility to run your own business, for small businesses like therapists that want to break off on their own, or a yoga instructor or a juicer or a chef. It’s addressing your economic and occupational wellness. In short, the seven areas are what we consider to be a “well” person…

Emma:

One of the things I love about enBloom is that it’s a very intersectional organization. It addresses intersectional issues and it provides intersectional solutions…

One of the intersections it meets is food justice, which I don’t think is an area of justice a lot of even activists and organizers are familiar with. Sometimes I’ll get strange looks when I reference my work in contracting [on food justice]. So, could one of you explain what food justice means to you, and what enBloom does to address that specifically?

Michael:

…If you would’ve asked me what I thought about “food justice” six months ago, a year ago, five years ago, totally different answer. But in today’s world, when we are looking at what’s going on geopolitically, within the United States as well as throughout the world, we’re starting to see how decisions made by people in power are starting to trickle down to the dinner plates at a rate that we haven’t really seen before, right? The economy is becoming more and more interconnected. What’s happening in Europe right now is directly impacting our food that we get here in the United States.

enBloom building their legacies and cultivating future changemakers through their program, Schools enBloom!

So food justice to me, it looks like having a world where you have fair judges and a fair system of accountability such that when we find offenses in the way that food is being processed, the way that food is being grown, the way that food is being distributed, the way the food is being labeled, that there is a trusted process in place where that situation is quickly rectified.

I’m trying to say that, being the most politically correct as I possibly can, because things are changing and there are things that change your mind…

Joi:

I think what I heard is, us being able to participate in the system, everybody being able to participate in their food system, from seed to table. Right now, it’s not like that.

Like I said, land loss is real. We’re losing land and don’t have the opportunity to grow food. We’re really disconnected from how to grow food; we don’t have access or even knowledge of foods that are historically from our culture. We don’t even necessarily know where we’re from; so it’s just really that disconnect. But, we’re still consumers in the system, so it’s the opportunity to fully participate in nourishing ourselves.

Michael:

…and pre-interview when, when the word “Indigenous” came up? As a backdrop and a framework, how do you bring that Indigenous way of dealing with different folks in different tribes in different parts of the world, and it worked?? <laugh> Right? Not to romanticize anything, but things worked, and people lived in harmony with the land. It wasn’t a problem.

…it’s not a problem with the resources. The resources are abundant. But why is it that people still suffer with hunger? What is actually in the way, that’s stopping foods, fresh fruits and vegetables, getting to Baltimore City?

As a quick tangent, why I keep on harping on this: I used to live in Baltimore City, and I was right downtown. There are no grocery stores within a five mile radius. And with the backdrop of growing up where I grew up, we always had a small family garden. I’m not saying I’m perfect, but I’m used to having access to fresh fruits and vegetables. When I was in New York, they used to have the bodegas on the corner. In Baltimore, that lifestyle does not exist, right?

Joi:

Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>.

Michael:

But I know that there are fresh fruits and vegetables in this state, right? Because when I would leave from Baltimore, I would come out to [Baltimore] County, go grocery shopping, and have to drive back to Baltimore. So the fruit is getting here, but it’s not getting to where it needs to be. So what really is the problem?

Emma:

…There’s a definition that a food justice organizer named Karen Washington came up with, which was “food apartheid”. She used that to distinguish it from a food desert… it specifically includes that societal context of, white supremacy makes it more difficult for communities of color to get access to fresh fruits and vegetables, to food that is nutritious and affordable at the same time. I think it’s a powerful expression.

Joi:

Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. Yes, I have heard that.

Emma:

…Where does enBloom fit in the fight for racial justice? How does it address historical agricultural struggles between the US government and marginalized communities, particularly the Black community?

Joi:

I think it’s a “we’re all in this together” type of situation. It’s easier to work collectively than it is individually. The idea of a community land trust, for instance – it’s expensive if we’re talking about Anne Arundel County, to go and purchase land on your own, individually. We would love to be gifted land, but we have to take other means to be able to do it collectively, create access.

While we can’t go back and undo what has happened in the past, what can we do to move forward? <laugh>. I laugh, I say, “This is a good time to be Black”, because there’s a lot of awareness. There’s a lot of resources. I don’t know if the time is ticking on that. It feels like a window is closing, but it is a good time to take advantage of the awareness and publicity that’s around to try and right things that have happened in the past.

I feel we’re more empowered as we have more education, more connections, our networks are strengthening, growing. We may not have wealth and resources that were passed on to us, but we have the knowledge and the connections now to, more so than ever, change the trajectory.

I don’t know if I really answered the question, but that’s one way that I see us being able to affect racial justice now, is using the tools and resources that are available to us, and our education… to help change the trajectory.

Michael:

Just to add onto that, a part of our strategy is to actually acquire land en masse. So land that is bought here in Anne Arundel County and other counties and cities through Maryland and further, they will be structured in a way that they’re owned wholly into perpetuity by people of Indigenous backgrounds. Once you get the land, that’s great; but understanding, again, the world in which we live in, how you structure that land, from an ownership perspective…makes a difference…

We’re going through it in our family right now, and I have long since made the decision that property assets should not be owned in people’s names. That’s one of the ways that we’ve lost land, not even in a way that’s necessarily dubious or unfair.

It’s just like, “Nah, you shouldn’t have owned, now you got five kids, now those kids died, but nobody took the time to actually settle the wills. So now you gotta sell it at bottom prices, because the economy’s different now”. Coming up with $2,000 a year for taxes, it becomes a burden for people… People are saying, “You know what, just sell it for pennies on the dollar.”

Whereas if there was a structure in place, and an economic engine that generated revenue to maintain structure… you’re cruising on autopilot.

Joi:

Yeah. That’s really been one of the most intricate and time consuming parts of building this ecosystem, this machine, if you will – one of my farmer friends would say the Voltron –

is using the law and the structures that currently exist creatively, in a more democratic and collective manner. So that’s having to work with attorneys and work with different folks who are experts in these things. I think that goes back to us doing it together – many hands make light work.

We can’t all be expected to be the experts in all of the things that it takes to run a farm or to run a wellness facility; but each individual can contribute something to that recipe, to that Voltron. Together, we can be more effective than we would individually.

We do put an emphasis on historically marginalized communities, specifically the Black community, because we believe that those who are least served, when they’re empowered, when they are doing better, it’s better for the entire society. But enBloom is not just for Black people, it’s for people who support the wellness of our community that is going to uplift everyone.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Part 2 will be up next week! Thanks for reading!

References:

- “A Brief History of Black Land Ownership in the U.S.”

- “The Contemporary Relevance of Historic Black Land Loss”

- “Social Justice Vocabulary”