Cultivating Legacies: An Interview with enBloom (Part 2)

Here at The Magpie, we spend a lot of time exploring the local history of Anne Arundel County, Maryland, where we were founded. We prioritize the history of advocacy and racial justice, and have years of experience in studying local histories of systemic racism. Through this work, we have found that as endless as human history may seem, all of it is connected in some way.

History in general is so interconnected, it can be frightening (exhilarating) sometimes. You will find yourself making connections between seemingly disparate subjects more frequently than you think.

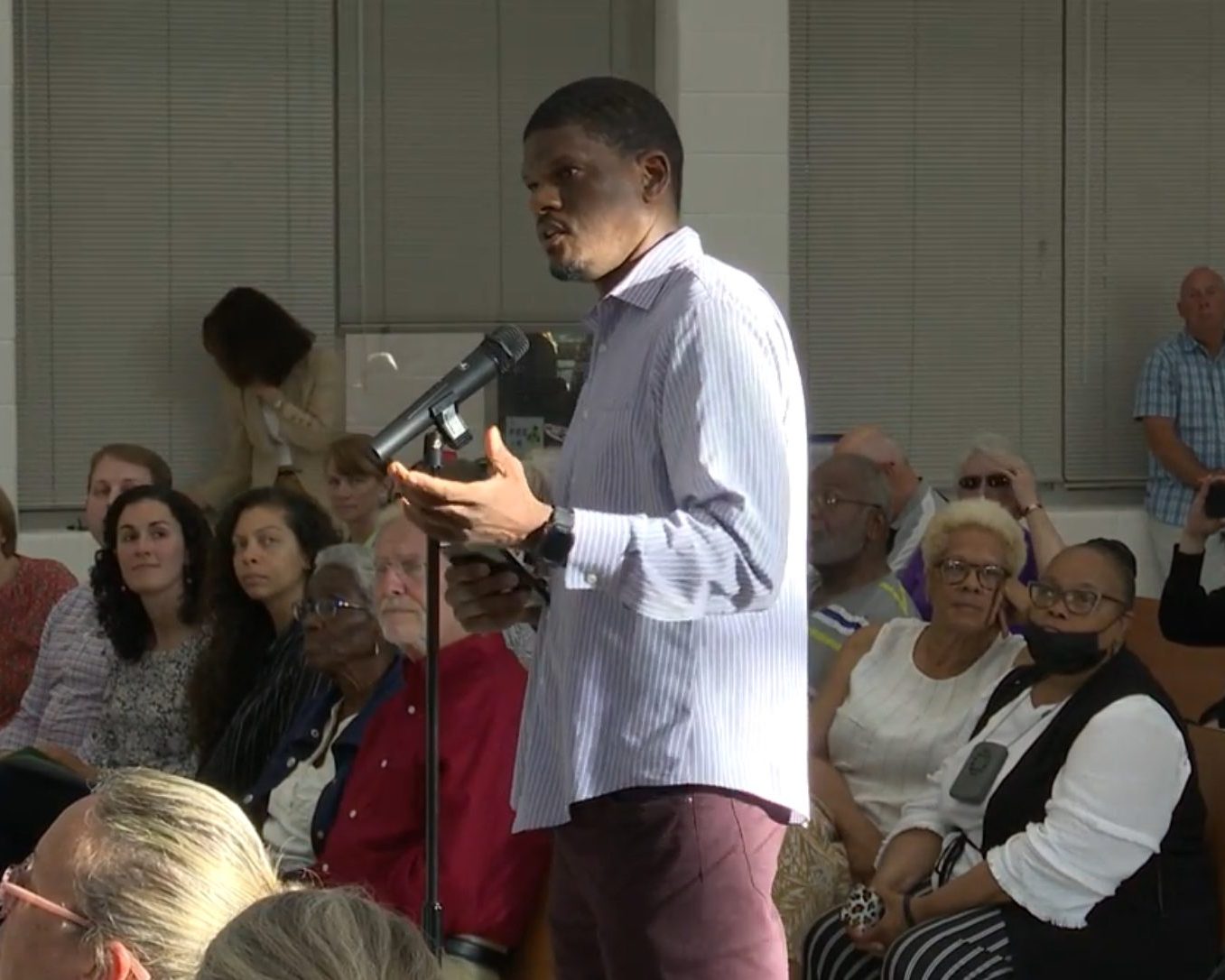

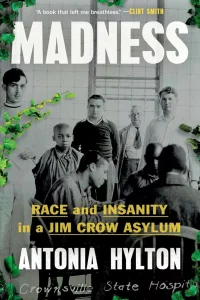

It is through this interconnectedness that allowed this interview to come into being. I was first introduced to enBloom co-founder Joi Howard by education activist Laticia Hicks. The three of us had independently decided to go to a local stop of the book tour for Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum by Antonia Hylton.

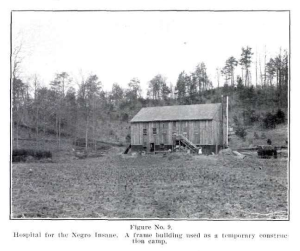

Both Joi and Laticia were serving on the County Commission for the administration of the abandoned grounds of an asylum in Crownsville, the topic of that (now best-selling) book — an asylum that stood just down the road from that stop on the tour. While it is now known as Crownsville State Hospital, it was born as the Maryland Hospital for the Negro Insane, the state’s first asylum for Black “patients”.

As the three of us discuss in this part of the interview, Crownsville earned a dark reputation over its decades of operation for their mistreatment of patients and oppression of Anne Arundel County’s Black community. After years of relentless advocacy from local organizers and historians like Janice Hayes Williams and Faye Belt, those injustices have finally begun to be addressed by County government (emphasis on “begun”).

The enBloom team recognized the opportunity for healing this revived government interest could bring. If the County were to return Crownsville to the community that was oppressed by its existence, organizers and nonprofits like enBloom could transform the grounds into a wellness park. It could honor and memorialize the history of Crownsville, develop community gardens to increase sustainability, and employ Black medical and wellness providers that give free services to the community.

Well, as Michael says later, “Negotiations continue” on this front. Regardless of how receptive a government is to antiracism and progress, it is often an uphill battle to make good trouble happen as soon as it should. In this piece, Joi and Michael will share just how much of an uphill battle it has been for them and their future plans to continue their fight.

We support community calls for the property of Crownsville to be returned to the Black community of Annapolis and Anne Arundel County, MD, and for administration of its property be overseen by descendants of its patients and others negatively impacted by Crownsville’s barbaric practices.

Be sure to check back for more coverage of Crownsville Hospital in the near future! This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Emma Buchman, she/her (Editor, The Magpie):

Mike, you referenced a specific way that generations of Black families and communities have lost access and ownership of land property that belong to them. Can you name a few other ways land has been historically stolen from the Black community? And please, feel free to mention the more dubious ways that was done…

Michael Ligons, he/him (Co-founder, enBloom):

Straight up theft, not honoring contracts, some instances murder. We’ve seen the history of what’s happened just here in America and in how other nations have lost land. If you think [about] apartheid and colonization, <laugh> it baffles me. It really, really baffles me. But as enBloom, we understand the historical backdrop. We know that we cannot undo what has been done.

But we will fight to make sure that, to the best of our ability, it does not happen again. And then where there is an opportunity to get restitution for those people that were impacted by those decisions, we’ll also fight to make sure that they get their just due on compensation.

Joi Howard, she/they (Co-founder, enBloom):

Sometimes we weren’t necessarily the landowner on paper, but your blood, sweat, tears, and toil and cultivating the land, nourishing it with no compensation or very little compensation, I think, is another way of land loss…

You don’t ever have enough: it’s just making ends meet so that you can’t acquire your own land. Things were put in place to make that intentional. Now that we know that, we have all this evidence, it’s not a secret. What can we do? That’s the repair: knowing what we know, how can we remedy that? That’s why being gifted land is a strategy that we talk about, because there are folks out there, institutions and entities, that are open to those options.

On the left is the book cover for Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum by MSNBC contributor Antonia Hylton. On the right is a photo of Crownsville patients working in a field in the 1910s.

Despite the hard work Crownsville patients did, from weaving award-winning baskets to farming for their own food, they were never even remotely compensated for their work. (Image credit: Madness book cover – Hachette; Patients – Maryland State Archives)

Emma:

That’s actually a great transition into me asking you about Crownsville!

Crownsville Hospital is something that we want to talk a lot about on the blog, but this will actually be the first introduction to it. So the first part of this question is… what is Crownsville Hospital? Why are we talking about it?

Joi:

[I was] going through a lot of transitions – [my family] moved to Crofton on December 31, 2015, we were in Bowie before. I have been in mixed neighborhoods and around lots of different types of people before, but for whatever reason, moving here to Crofton was one of the first times that I really felt othered.

I had two young kids, I was really struggling, trying to figure out how to be the mother that I wanted to be to them. [I started] a new job and living in a new house. My father had passed away around that same time from ALS. Just going through a lot of transition and, truthfully, drinking a lot. And just realizing that this is not the example that I wanna set for my kids.

Once you’re aware of how trauma and things are showing up in your life, you have the opportunity to address it. I was on autopilot for a good amount of time, but once I started to have some awareness, I’m like, wait a minute. This is not the way that I want this to go.

Around the same time, my youngest daughter was having a lot of ear, nose, and throat infections, and the doctor wanted to put her on, like, the fifth course of antibiotics. Once I recognized that one course of antibiotics will knock your immune system out for a whole year, I didn’t wanna do that anymore.

So we started going to a natural path. I started to really invest in my own health, but at the same time, I came across Crownsville, which was only 15 minutes away from my house…

For some reason, one day I came across it, didn’t know anything about it; but I saw the sign, saw all the dilapidation… and just was really drawn to the site, the building itself, and didn’t really know why.

Once I did a little bit of research and realized that it was formerly called the “Hospital for the Negro Insane”… I don’t know, a spark, a light… I truly feel called to it. I can’t explain what it was, but I did a deep dive and just [became] very engrossed in the history of the hospital and all things Crownsville.

[I] learned it was more than 500 acres that was owned by the state at the time. I learned that the patients grew their own food and made their own clothes and were self-sustained, and had the second largest basket weaving industry in the state at that time.

But realizing that there was also a lot of ill treatment of the patients there. They weren’t paid for their labor. A lot of them died. This was an opportunity to honor the self-sufficiency that the patients had to a certain degree, but then also offer this community-led wellness that the patients weren’t, that they didn’t receive there.

The thought is no one’s gonna take care of you like your own will. If this was an eco-hub, a wellness hub where Black practitioners or practitioners of color, and farmers and everyone involved in this food chain system… we’re leading this effort that was an opportunity, a real tangible thing that we could do to have large scale impact, not only in Anne Arundel County, but be the example for other municipalities you know, across the United States and beyond.

Emma:

They grew their own food, they had an amazing basket weaving industry, and they also built their own hospital…

Joi:

Exactly. That’s still standing today! So that craftsmanship, you know, it’s an amazing story.

Michael:

If I could just interject, something else that underlines this – this is what we call “the insane”… How do you pay people back for that?

Joi:

…They were classified as insane, but look at what they can produce. To me, it shows that everybody has value. Everyone can contribute something, can be a contributing citizen.

Michael:

Yeah. But to that point, we know how [some of] the stories go, at least from what I can understand: someone had a bad day, but they might have been in downtown Baltimore, and they acted out in such a way that made some people scared. Then they would call the cops, and the cops would come and they would say, “Oh, no, you’re not acting right, we’re gonna take you down to Crownsville.”

This is a functioning person of society under other circumstances, but now you’re put in a system where you’re almost forced into labor that you’re not gonna get compensated.

We’ve dubbed you insane, so now we’re almost justified, because it wasn’t really work – it was “rehabilitation”.

But then, why do you take the baskets down to the street and sell them for $20? That didn’t go back to them or their family…

It’s happening now. Like, imagine Sotheby’s – they might have a basket that’s 400 years old that’s from Africa, right? They’ll sell it for $4.5 million or whatever. How much of that $4.5 million is actually being funneled back into the community where that was taken? What really happened to that labor? These buildings down there at Crownsville, they’re made of brick. They’re strong.

Joi:

Clearly invaluable.

Michael:

Right, right. So how much of that real estate deal is going back to their descendants? You know? When we talk about this restorative justice, how do you actually restore justice?

Emma:

The other thing with Crownsville is once you were sent there, you really didn’t leave. They kept you there, even if you didn’t need to be there. Even if you had been someone who was mentally unwell and you were treated, and they’re like, “Oh, I’m fine now.”

“No, you still stay here.”

”…but I’m fine now!”

Michael:

Exactly, yeah. Now it’s no longer healthcare, it’s prison. It’s the industrial complex.

It’s the same story. It really is the same story just told in a different type of way, you know? Slavery, even if you had your traveling papers, quote unquote – you did everything the “right way”, you did it by the law – [still] depends on who you ran into the road. They still put you in shackles. So, again, understanding the history of what it took and the cost of it, and the people who paid the cost.

Well, their descendants are here. We should do everything that we can do to make sure that they’re taken care of.

The campus of Crownsville State Hospital may have been abandoned, but the fierce love of activists and community members have ensured that the memories of its former residents are never forgotten. Some of these names include Janice Hayes-Williams, Faye Belt, Rodney Barnes, Scotti Preston, Laticia Hicks, and Joi Howard, & Michael Ligons.

Joi:

Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>… We’re talking about Crownsville because it’s an opportunity. It sat dilapidated, no one cared about it, essentially, for 20 years. When it closed, people took cuts out of it immediately. Half of it went to Bacon Ridge for a bike trail… Then there’s some organizations that had claimed their stake in it, and then the rest of it just wasted away, ‘cause no one cared about it. Even though, like we all pointed out, the craftsmanship of this building that was built so long ago, more than a hundred years ago, is still standing because of who was there. It was deemed as not worthy enough to maintain or to repurpose.

We’re talking about it because we see it as an opportunity for the community. It’s not a throwaway…

Return it to the community. We care about it. We have history. I have family members, so far I know of three family members that were patients there. At least one of them died there. That is of importance to a lot of people in our community. It’s not a political chess piece.

Emma:

Yeah. And too often they treat it that way. What’s the status of enBloom’s plans at Crownsville? Are there any updates you can give?

Joi:

Oh, yeah, that’s a good question. The County is in the process of completing or finishing the master plan. I feel like it’s almost a whole other conversation about the County’s process…

Michael:

You almost want to say, “Negotiations continue”.

Joi:

They’re in the part of doing the master plan; it is really not clear what the next steps are. So, we have just been staying involved in the conversation and talking to those that we can to make sure that we have a seat at the table when it comes time to making decisions on who’s going to get land or operate things there.

So, yeah, definitely a “To Be Determined”, but staying in the conversation. A lot of it is not so transparent in the County process.

Emma:

…Are these roadblocks you’re experiencing with the County similar to roadblocks you’ve experienced with other projects enBloom has tried to do?

Michael:

We’ve had some successes and then… I say that “negotiations continue” tongue-in cheek, right? Because we know what we’re up against. Some negotiations go through rather smoothly. We can see progress almost immediately.

Then other times, when we have to deal with bigger interests, it feels like there’s a lot more activity happening central to where we are and we’re fighting to make sure that we’re not marginalized in the process.

Joi:

Well, somebody said to me, “Joi, you chose the hardest county in the state to be doing a project like this!” I could appreciate that somebody was validating that, because it definitely has felt super hard. A lot of people would say, “Go to Baltimore, go to Frederick,” go to places where they’re trying to give away land. But… that’s not where we live. We live here.

…Schools enBloom is heavily, heavily reliant on the relationship with Anne Arundel County Public Schools: kids are at schools, schools have lots of land, gardens are known to be good for all the things in education. But it feels like a fight with the facilities to grow food at its designated spaces. For Georgetown East, for instance, it’s just been an uphill battle.

So yeah, it definitely feels like there’s a lot of control and power being exercised. It’s a lot of who you know and making those political connections. I have definitely felt a challenge in lots of different areas in working with Anne Arundel County, but I’m hopeful.

But I also hear that’s just part of government and part of politics. I’m hoping, not even hoping, I’m intent on this being realized within my lifetime. Something that my kids can utilize, that myself and my family can utilize. This is not something that we wanna see come into fruition 30 to 40 years from now…

Emma:

…What advice would you give to activists or organizers who want to do something similar to enBloom in their own communities?

Joi:

So, there’s twofold. If we’re talking about locally in Anne Arundel County, I would say let’s partner, let’s join together! Again, we don’t have to do it alone. We don’t need to, and we shouldn’t want to. It’s a lot of work. It’s a big lift and we really are better together. So if we’re talking about local activists, let’s connect and figure out how we can do this together.

If it’s people who are not who are not within close proximity, I would say balance…

That’s been one of the biggest challenges for me over these past three years, particularly when the public became more aware about Crownsville and the County’s process started to move. If it’s something that a lot of people are talking about and the timeline is being driven by others, I think there is a feeling that you have to be there. You have to be at all the things. For me, it has felt like to the detriment of my family. It’s a lot of the meetings would be at seven o’clock, and you have to be there in person or doing lots of late night calls. It’s just a lot of pieces to it. And I feel like every time I’m away fighting for larger community issues, that I’m taking away from my own household.

So I would say have balance and listen to yourself. Be present and really be in touch with how you’re feeling. If something is not feeling good, acknowledge that and take the time for yourself.

This summer, I really have unplugged a lot, from especially County-related work. I wanna preserve myself, <laugh>, and I don’t want to harm myself for the sake of healing. [I’m] really trying to make space for how I feel and balance out what had been imbalanced over the past six months of not paying enough attention to myself and my home.

Emma:

Yeah. We don’t want you to hurt yourself. We need you.

Joi:

Mm-Hmm. <affirmative> <laugh>. Thank you. Yes. I need me too, <laugh>.

Emma:

So the last question I had was how can people get in touch if they wanna get more involved with enBloom?

Joi:

So we have a website: enBloom, E-N-B-L-O-O-M.life. That’s a good place to start. It does need to be updated. We have a partnership with a university and have interns helping us do an audit of our website. So there will be updates to it, but that’s a good place to start.

Then emailing us at be@enBloom.life will get you to me and Mike.

We need someone to help with our social media. We have pictures from all the things that we do; but it’s a lot to manage, especially right now on volunteer power. That is something that I talk about a lot, around agriculture or community gardens – the existence of it shouldn’t be dependent on free labor, volunteer labor. Neither should this work. Working to get funded to be able to support a team has been definitely high on the list. So social media, we need somebody to help with that, but we do have an Instagram. But website and email are definitely the best two options.

Emma:

Amazing… Well, thank you for taking the time to speak with me!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

References:

- “Crownsville Hospital: Timeline”

- “What a Jim Crow-era asylum can teach us about mental health today”