Mental Health Checkup: Binge-Eating (2)

Introduction from Emma the Editor

Welcome back to our newest series, “Mental Health Check-Up”. Here at The Magpie, we believe that mental health is as important as physical health. However, the stigma and ignorance around mental illness engrained in American society has created an environment of fear and distrust when it comes to expressing their concerns.

Today, we rejoin our contributor Sarah Jane as she shares about her recovery journey with binge-eating. As you’ll read, serious challenges like mental health issues can be challenging with many steps forward and backward.

In Part 2 of her story on her journey with binge-eating, Sarah references numerous healing and therapeutic practices, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT). Sidenote – as someone who suffers with OCD, I too have found DBT to be very helpful.

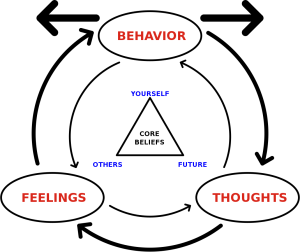

CBT is a well-known therapy among many sufferers of mental health issues. It is a therapy technique that recognizes the way that social factors impact mental health, in addition to psychological and biological factors. It focuses on reframing cognitive distortions and acting based on the reframing. It is very successful in treating depression, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorders.

DBT is shown to be extremely helpful for many – it is geared more towards treating personality disorders and interpersonal conflict. Mindfulness and coming from a place of radical acceptance are key components of DBT.

But these are only two of the many ways to get the benefits of therapy, and they might not work for everyone. As Sarah demonstrates, it takes time to find the right regime for you, and no practice is better or worse than another. And whether they follow more of a Western or Eastern tradition, doesn’t matter: if it works for you, it works.

We hope that Sarah’s bravery in sharing her journey gives support to someone else in a similar situation, and be sure to keep checking The Magpie to see more from Sarah Jane in the very near future!

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, you can find a helpline and other resources through the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD).

Part 2: Out of It

By Sarah Jane, MOF Contributor

Sarah Jane is a tarot reader, retreat leader, and workshop facilitator who primarily works with women, although she also works with men. She believes spirituality, in addition to more conventional therapy and recovery programs, can help those suffering from trauma to release and become more whole.

TW: in-depth discussion of binge-eating disorder; references to alcoholism and substance abuse

Over the course of my life, I have been through sex trafficking, a brain tumor, weeks of severe sleep deprivation, abusive relationships, addiction, and a diagnosis of Bipolar…

Still… still, recovery from an eating disorder is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.

Food issues are so insidious, so all consuming, and so reinforced by society, that finding a way out seems impossible. Then it comes in fits and starts, steps ahead and behind, jumping across stones in a river.

I didn’t really try to diet as a kid or teen. My weight crept up and I ignored it. Sometimes I was softer, other times the stimulants I was on kept me small. People would make comments both praising and criticizing, but it didn’t mean much to me: I had other things to focus on, namely surviving.

I had a fear of cooking, which meant I was at the mercy of others for my food. This obviously posed a multitude of problems with self-reliance and an unhealthy relationship with food in general.

Adulthood trauma, however, brought weight; and I began the dance of putting on and losing weight and back again.

At 29, I entered a 12-step program for my alcoholism and drug addiction. This was, in part, due to my wish to lose weight: I knew I couldn’t do that if I was drinking 12 drinks worth of calories, losing control of my eating while drunk, and needed to eat to soak up alcohol during hangovers (not to mention the munchies when I used cannabis). At the time, I was simply focused on moving the number on the scale. The pain of being morbidly obese partially drove me to give up all substances and embrace a “spiritual” way of life.

Through this program, I met a woman who had lost almost 200 pounds. I had never met anyone who had done this before. She told me she knew of something that could help: a version of the 12-step program that focused on food.

I was hesitant at first. The woman was brusque and seemed to be a bit judgmental about people who carried extra weight. But I was 300 pounds and desperate.

The weight came off. Of course it did. I started walking in the pool every morning, which I loved (and still do). But then I also ran. Twice a day. I destroyed my knees, my hair fell out, I was always cold (which the women I knew in this program jokingly called “the chill”), and I bruised easier than a peach.

So, I followed her instructions. I would wake up every morning and call her at 6 o’clock – not 5:59, not 6:01. In fact, when I called at 5:59 the first morning, she yelled at me: “My time for you is exactly 15 minutes, starting at exactly 6:00!”

She told me I needed to write down my food the night before and then read what I wrote to her in the morning. It was three meals, no snacks. All food was weighed and measured with scales to the ounce. I was not allowed to eat in restaurants or have anything with sugar, artificial flour, or caffeine. I was only to have a certain amount of meat, salad veggies with dressing (also weighed), and a cooked vegetable.

If I differed from what I committed to eating (fish instead of chicken, carrots instead of brussel sprouts), I needed to call her and tell her. If I did this three times, she would “fire” me.

I was expected to go to three 90-minute meetings per week, no exceptions (even though some of them were at 7:30 on weekday nights over 45 minutes away in DC traffic). When a meeting conflicted with my job, I had to take time off. every week. And, I was not allowed to share in these meetings until I had three months of eating perfectly.

I had to call three people a day for fifteen minutes each. I needed to sit in silence for 30 minutes every morning. The list goes on.

The weight came off. Of course it did. I started walking in the pool every morning, which I loved (and still do). But then I also ran. Twice a day. I destroyed my knees, my hair fell out, I was always cold (which the women I knew in this program jokingly called “the chill”), and I bruised easier than a peach.

Forget finding joy in food: I wasn’t even allowed to combine vegetables. “Slipping up” terrified me. It became clear: I had traded one eating disorder for another.

Eventually, the idea of vegetables made my stomach turn. I hated the thought of eating, of gaining weight, and of being full. My anxiety turned to self-satisfaction at my “discipline.” I narrowed my food to one cheese stick, one piece of chicken, and a handful of carrots per day. I was still running twice a day.

But I was no longer losing weight: my metabolism was destroyed. So, one day, I had a latte and stopped doing the “program.”

— — —

My next few years were basically spent tormenting myself: I couldn’t do the program, I couldn’t eat “perfectly”. I tried tens of diet programs, including the restrictive one, again and again. I would gain and lose over 120 pounds three times.

After my last bout with the restriction diet, I ate M&Ms one day and never stopped eating. I went over 300 pounds for the first time. I was terrified, and full of an ungodly amount of shame. I had only the smallest glimmer of hope, the tiniest bud flowering within me. I prayed that would be enough to keep me alive. It barely did.

I worked with therapists and support groups, but made no headway. As other parts of my life improved, my eating did not. I healed so many hurt parts, but I still couldn’t feed myself. I went to holistic nutritionists and would eat desserts in the parking lot. I was clinging to something, and I didn’t know what.

Eventually, I left the program for the final time. One good thing that therapy had given me was the ability to soothe myself, to talk to wounded parts of myself, to forgive myself.

So, I used that as a jumping off point: I slowly started loving myself. I learned that for me, shame would never bring a lasting truce with food. I needed to feel my feelings and change my thoughts. I was finally honest with my family and friends about my struggles.

I found a combination of practices that finally worked for me: self-love, cognitive behavioral therapy (changing my negative self-talk to positive), dialectic behavioral therapy (moving away from the black and white thinking that made me feel like I was a good girl or bad girl depending on what I ate), and a loving spiritual practice.

This vital combination allowed me to look closely and honestly at myself: I was putting on weight to keep men away due to my trauma.

The truth is, I needed both Eastern and Western medicine. I needed to heal mind, soul, and body. And I needed to start from the still, quiet place deep within my spirit that still loved myself.

I wish I could say that the only person I was hurting was myself, but the world doesn’t work that way. Because of my suffering, my family and friends suffered too. But the beautiful thing was that they could now revel in my healing.

I learned about intuitive eating: feeding myself when I was hungry and learning the difference between actual hunger and boredom, sadness, or other “bad” emotions. I learned that feeling emotions wouldn’t kill me. Intuitive eating was revolutionary, but it was not something I could do before I was really ready to excavate my trauma.

I eventually went to a hypnotherapist and shaman who believed that recovery was possible through metaphysical means. I blossomed in this space. I often say that metaphysics such as hypnosis and shamanic journeying did more for me in three months than 30 years of traditional psychotherapy.

The truth is, I needed both Eastern and Western medicine. I needed to heal mind, soul, and body. And I needed to start from the still, quiet place deep within my spirit that still loved myself.

It wasn’t easy. Some days it still isn’t. Harsh thoughts can take over. Sometimes I eat late at night, sometimes I eat too much, sometimes I eat out of sadness and boredom.

But I have, through being kind to myself, reached a truce with food. When I eat more than I want to, I still love myself. My people still love me. The universe still loves me.

I have taken the morality out of my eating.

I am at the start of a completely different journey. I have lost some weight, but it doesn’t make me better than when I didn’t. I am embracing health in every facet of my life. The wounded child in me deserves that, and I owe her everything.

At our next Mental Health Check-Up in April, Sarah will be back with us to share her experience as someone diagnosed with bipolar disorder.