The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone: A Mystery of Mysteries

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

By Emma Buchman, MOF Digital Content Director & Blog Editor

Emma Buchman is the director of March On Maryland, digital content director of March On Foundation, and editor of the MO Foundation Blog. She also works as a writer and researcher at Studio ATAO. Emma has studied Chernobyl for over four years, focusing on the history of the accident and its liquidators. Emma also contributes to a website that collects any and all information on the Chernobyl disaster, specifically sources contemporary to the time of the accident and memoirs from liquidators.

Part 2/11 of the series “On the Safety of Storks”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Thy soul shall find itself alone

‘Mid dark thoughts of the grey tombstone;

Not one, of all the crowd, to pry

Into thine hour of secrecy.

–

Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not loneliness – for then

The spirits of the dead, who stood

In life before thee, are again

In death around thee, and their will

Shall overshadow thee; be still…

–

…Now are thoughts thou shalt not banish,

Now are visions ne’er to vanish;

From thy spirit shall they pass

No more, like dewdrop from the grass.

–

The breeze, the breath of God, is still,

And the mist upon the hill

Shadowy, shadowy, yet unbroken,

Is a symbol and a token.

How it hangs upon the trees,

A mystery of mysteries!”

Spirits of the Dead, by Edgar Allen Poe

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

TW: mentions of animal death, suicide

The Chernobyl (Chornobyl) Exclusion Zone – one of the most unique and mysterious places on the planet. At its center lies what remains of Chernobyl’s fourth block, entombed in the world’s most expensive coffin. For over 37 years, the ruins of the plant have sat looming over the Exclusion Zone, a ghostly vision permanently etched into the Ukrainian countryside. The ghost town of Prip’yat rests nearby, a cemetery for a dead city.

But it wasn’t always like this – Chernobyl’s fourth block was not always a symbol of darkness, confusion, and death. In fact, to many, it was an inspiring thing to behold.

Before it was the epicenter of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, it was the fourth reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. It was the pride and joy of the Soviet civil nuclear industry, whose motto was always, “bigger, badder, and even bigger than that”. For many of the staff members at the plant, working at Chernobyl was a dream job.

The adjacent city of Prip’yat stood proudly at its side, “a true Soviet dream town” as BBC Science Reporter Victoria Gill described.

Obviously, this changed after the accident on April 26, 1986. In a few moments the reactor was gone, along with the roof of the building and one of its workers (so far). Once the Chernobyl Commission made it onto the scene, the interment of the fourth reactor began, and the Zone of Exclusion was conceived.

The Chernobyl Commission arrived in Prip’yat at 8PM on the night of April 26, immediately relieving the shellshocked plant staff who remained (many of them were hospitalized at this point; those with severe radiation exposure were transported to Hospital No. 6 in Moscow). Chernobyl Commission Chairman Boris Shcherbina immediately set to work managing the mitigation effort. Among the many immediate issues to confront on-scene was whether they were going to evacuate Prip’yat.

Academician Valery Legasov would be the first to publicly call for Prip’yat’s evacuation, but other scientists were equally vocal and insistent. Ultimately, the Commission sided with Legasov and moved to evacuate Prip’yat.

In the early morning hours of April 27, Shcherbina called his boss First Minister Nikolai Ryzhkov to report on the situation “wearily and with anguish”. When told of the Commission’s decision to evacuate Prip’yat, Ryzhkov authorized the evacuation without hesitation. He instituted a 10 km (6mi) zone around the immediate perimeter of the plant for evacuation and liquidation.

Around 50,000 residents, many of them families building their lives, were evacuated on over a thousand buses that drove from Kyiv. They were told the evacuation was only temporary, a lie that haunted Legasov.

In truth, they would never return to Prip’yat again. It would be a trauma in and of itself, even apart from the radiation. Among the many precious things people were forced to leave behind were their beloved pets; they would eventually become the first new residents of this fast-growing zone of alienation.

After Prip’yat’s evacuation and verifying that the reactor was no longer… well, reacting, the Commission’s focus expanded. A massive liquidation effort was carried out to mitigate the impacts of the radioactive fallout.

Liquidation tasks were myriad and dangerous. Many of them were also traumatizing and devastating to the liquidators who performed them. In total, an estimated 800,000 liquidators would risk their health and their lives to liquidate the accident and protect their people.

Among the more heartbreaking tasks was every animal lover’s worst nightmare: euthanizing the pets left behind to prevent the spread of radiation. Ukraine’s Society of Hunters and Fishermen was enlisted to lend their expertise, and over 20,000 domestic and agricultural animals were killed.

Ryzhkov also headed the Government’s Chernobyl Task Force from Moscow. Within a few days of the accident, Ryzhkov expanded the 10-kilometer zone to establish the famous 30-kilometer zone around the perimeter of the plant from which to evacuate surrounding villages and towns. Over 130,000 residents were eventually evacuated around Chernobyl in the early years after the accident.

The area of alienation would be expanded numerous times until it grew into what it is today: an area of over 1,600 sq miles (~4,200 sq km) in northern Ukraine and southern Belarus. It has been known by many names, but there are two that are most relevant here: on the Belarusian side is the Palieski State Radioecological Reserve; on the Ukrainian side, the Chernobyl (Chornobyl) Exclusion Zone (CEZ) (for now, we’re going to stay on Ukraine’s side of the fence).

In the decades that followed, life went on both within and outside of the CEZ.

On the outside, Chernobyl whistleblowers gave their careers and sometimes their lives to protect people from future accidents like Chernobyl, which were imminent without immediate intervention.

Liquidators got sick – some got better, some didn’t. Upwards of 120,000 of them would die by 2005. This included both Legasov, who died by suicide on April 27, 1988; and Shcherbina, who died on August 22, 1990 after suffering multiple heart attacks.

Thyroid cancer rates shot up in areas impacted by the accident, particularly in Belarus and northern Ukraine. The biggest increase was among children.

People tried to move through their trauma, and their fear that they too would fall victim to radiation poisoning.

The Soviet Union fell, and former republics reclaimed their identities. This was certainly true for Ukraine, who turned the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and the protection of the fourth reactor into an international effort of collaboration on nuclear safety.

Within the Zone, final liquidation efforts were carried out and the infamous “Sarcophagus” entombed the rotting reactor. (Sidenote: I prefer Legasov’s definition of “Shelter” over “Sarcophagus”, and he designed it after all; but I digress).

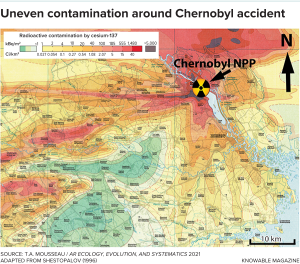

Liquidation efforts didn’t wipe away all of the radiation: they were never going to be able to decontaminate every part of the Zone.

To give you an idea of Chernobyl’s current radiation situation, here are a few measurements for comparison. Except where otherwise linked, all radiation measurements were retrieved by the author on November 25, 2023 at ~7:00PM Eastern Standard Time from SaveEcoBot.com. Measurements of distance were calculated using Google Maps at the same time and date.

To give you an idea of Chernobyl’s current radiation situation, here are a few measurements for comparison. Except where otherwise linked, all radiation measurements were retrieved by the author on November 25, 2023 at ~7:00PM Eastern Standard Time from SaveEcoBot.com. Measurements of distance were calculated using Google Maps at the same time and date.

See the radiation levels in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Normal background radiation:

~2,400 microsieverts a year

Cosmic radiation from a roundtrip flight between New York and Tokyo:

190 microsieverts/hour

Diesel Generator Station No. 2 (adjacent to 4th block):

7.49 microsieverts/hr

Administrative Building No. 1 (within plant complex):

0.26 microsieverts/hr

Storage facilities for solid and liquid waste (within plant complex):

3.01 – 5.29 microsieverts/hr

Red Forest (2.68km from plant):

35 – 40 microsieverts/hr

Prip’yat (3.31km from plant):

0.443 microsieverts/hr

Settlement of Buriakivka (15.2km from plant):

0.436 microsieverts/hr

Town of Chornobyl (15.45km from plant):

0.21 microsieverts/hr

In 2016, the Sarcophagus was replaced by the New Safe Confinement, a massive silver dome that was carefully slotted into place over the fourth reactor. It is meant to last 100 years. It will simultaneously protect the open core from exposing radiation while also dismantling the old Shelter inside.

As decades went by and people tried to keep the fourth block safe, the shadowy specter of radiation hung over their heads, forever making itself at home in their bodies and their spirits.

But in this most poisoned of places, something extraordinary seemed to happen: life returned in Chernobyl. More importantly, hope returned to Chernobyl.

Without humans to restrict it, Nature began to reclaim Prip’yat. Plants and wild animals moved into the abandoned buildings and made themselves at home. Dogs who managed to escape Ukraine’s Society of Hunters and Fishermen had litters of their own. Even people returned, both to work and live.

Today, the Zone is the third largest nature reserve in mainland Europe. It hosts a diverse community of plants, trees, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. All of them are chronically exposed to low levels of radiation, and endangered by the random “leopard spot” distribution of high-dose radiation described by Adam Higginbotham in Midnight in Chernobyl.

The liquidators have gone, and in their place is a community unlike anywhere else on Earth. It consists of many groups, some transient and some permanent. There are current plant workers who maintain The New Safe Confinement, though they live in the neighboring town of Slavutych.

There are also the permanent residents who moved into the Zone for various reasons: some are elderly women still tending their original homeland, (understandably) unwilling to give up their homes. There are some who are families that fled to the Zone to escape the violence of war, namely the war in Donbas that started in 2014.

At the same time, a transient community of knowledge-seekers has continually visited the Zone, among them researchers, scientists, and reporters. They travel from across the world to observe what they can of the impacts the accident had on the environment and what we can learn from it.

In this cemetery of human progress, Life has prevailed…

I started this piece off with Poe for a reason: Chernobyl is in itself a mystery of mysteries. Even collecting the most basic of facts is challenging, from the number of liquidators to the number of those evacuated from the Exclusion Zone.

It is the kingdom of paradoxes: a dead reactor at the center of a lively laboratory, a ghost town enveloped by a wildlife haven. And as lovely as that is in a poetic sense, practically-speaking it presents a challenge when trying to answer important questions.

Much like poetry, everyone has a different answer for these questions, and everyone has strong feelings why.

One of the most pressing unanswered questions since shortly after the accident has been, “Which side prevails in Chernobyl: Life, or Death?” Is wildlife safe there, or is it not? Is the lingering radiation more harmful to Chernobyl’s ecosystem, or is it benign enough to support future generations continuing to live in the Exclusion Zone?

Much like the Exclusion Zone itself, navigating this debate feels very much like wandering through Poe’s misty graveyard, where there is beauty in the macabre and light in darkness. “The mist upon the hill” is both the “symbol and a token” of what there is to discover, as well as what confounds us in the first place. It also obscures the full picture, never quite allowing us the whole truth (“Shadowy, shadowy”).

We want nothing more than to discover how that mist hangs upon the trees – how life has managed to thrive at all in Chernobyl after such a violent event. That pursuit is the core of this entire series.

Many scientists have devoted decades to studying the impact of ionizing radiation on plants and animals in Chernobyl. It is through their contributions that we are even able to explore this debate in the first place. For every article or research study declaring Chernobyl a new Eden, there is another that would warn about the very real negative impacts of chronic radiation on biodiversity.

Understandably, scientists are vehement to defend the respective “side” that their research most supports, sometimes even going so far as to throw personal insults. But this is only because at the heart of this intense disagreement is the mutual desire to use Chernobyl as a learning tool to further protect the planet.

I would argue that this mutual dedication to the protection of life is actually the answer to this mystery, albeit an unsatisfying one (though hardly any of the answers Chernobyl provides are satisfying). I believe it is the answer that can accept evidence from all sides and help keep the narrative on who the most important people are in this story: those directly impacted by the Chernobyl disaster, no matter their role in the ecosystem.

In the next part of the series, I hope to provide you with enough background on the science already done in Chernobyl that you feel comfortable drawing your own conclusion before thoroughly explaining mine.

Let’s see if we can even slightly unravel this mystery of mysteries…

Additional photo credits:

Featured photo: SSE-Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant

Top photos (in order): (1) Robert Baker and Ronald Chesser; (2) Igor Kostin / Sygma via Getty; (3) https://www.flickr.com/photos/105458023@N02, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons (2013); (4) SightTraider

Additional Reading: