Let’s Talk Reparations: An Interview with Reparations Educator Briayna Cuffie (Part 1)

“Reparation /re-pə-ˈrā-shən/: Noun. (1) repairing or keeping in repair; (2) the act of making amends, offering expiation, or giving satisfaction for a wrong or injury, something done or given as amends or satisfaction; (3) the payment of damages.” –Merriam Webster

“Reparation /re-pə-ˈrā-shən/: Noun. (1) repairing or keeping in repair; (2) the act of making amends, offering expiation, or giving satisfaction for a wrong or injury, something done or given as amends or satisfaction; (3) the payment of damages.” –Merriam Webster

There are many memorable quotes and themes from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. One theme that seems to be frequently omitted from mainstream commentary of this speech is the repeated reference to cashing a check that has long been owed to the Black community of the United States:

“In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check.” / “America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.” / “And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice…”

The “insufficient funds” were not a flowery reference for the sake of a good speech: they were an allusion to the U.S. government’s failure to make Black communities whole again after suffering through enslavement (and after enslavement, Jim Crow).

The funds were damages that the U.S. government refused to pay; and that check represented the reparations owed and promised to formerly enslaved Black people and their descendants, a check that has bounced over and over again.

Reparations seem to be a topic that not a lot of people want to talk about, particularly the white people who are supposed to be paying them.

But the topic of reparations has picked up in activist circles in recent years, particularly in 2023. At The Magpie, we believe that reparations are one of the most crucial elements of overturning white supremacy.

As such, I was delighted to do my first interview of the year on reparations with Reparations 4 Slavery’s Equity Advisor (and a former classmate!) Briayna Cuffie.

Briayna serves numerous roles in the Annapolis community in central Maryland. Some of them include local historian, racial justice organizer, and community advocate for the town of Eastport, a once thriving Black community that has been heavily gentrified.

I first learned about Briayna’s work on reparations in the summer of 2023 at an event organized by our local SURJ chapter – SURJ of Annapolis and Anne Arundel County (SURJ3a). Briayna explained that she founded Reparations 4 Slavery with her counterpart Lotte Lieb Dula as a repository of educational materials on reparations and combating white supremacy through confronting our history.

We thought that speaking with Briayna would be the perfect way to start The Magpie’s conversation on reparations, especially since she and her partner specialize in what they call direct repair.

In Part 1, Briayna explains what reparations are and the importance of understanding history in giving and receiving reparations.

Be sure to watch Briayna and her colleague Lotte in the new documentary The Cost of Inheritance on YouTube.

Check back for PART 2 on February 29th! *This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.*

Emma Buchman (Editor of The Magpie, MOF Digital Content Director):

Without further ado, I’m just gonna jump into the questions. The first thing is to tell us a little bit about yourself. Who are you? Where did you grow up and what do you do now?

Briayna Cuffie (Equity Advisor, Reparations 4 Slavery):

Oh, me??? <Laugh> My name is Briayna, regularly known as Bri. I am from Annapolis, Maryland, specifically Eastport.

The best way to describe myself is that I am made of my ancestors. My entire career track – both career tracks, honestly – and my consulting all center around the family and women and people and community that raised me, that raised my mom, my grandfather, the last five generations of my family here.

Going back further, we’re a part of making Maryland what it is today. Everyone that I have researched, that led into the work that I do, have been in Maryland back over 200 years.

I am a community servant at heart; probably, arguably, a politician at heart, I just refuse to become an actual politician. History nerd is probably the best qualifier <laugh>…

Emma:

Could you explain what reparations are, both generally speaking and specifically how they apply to the Black community in the United States?

Briayna:

…While there are other forms of reparations that have been done [with] other ethnic groups, the first thought when people think reparations is to the descendants of those who were enslaved, or the descendants of chattel slaves – those forcibly trafficked from the African continent with the purpose of explicitly exploiting our bodies’ labor, any and everything possible, until we literally died.

The part that is most talked about when it comes to federal government reparations to the descendants of the enslaved is monetary. It centers around labor (you know, ’cause we were forced to work for free); and then after the end of enslavement – formal, social, and actual, because there were people still enslaved after enslavement legally ended – the short-changing of labor and wages in the era of sharecropping and Reconstruction. Then of course, there’s still the racial wealth gap that exists today because of that.

A lot of it centers on the lost wages and lack of access to all the resources that existed during the era of enslavement. I see more people talk about the Reconstruction era after enslavement: as they were trying to build lives for themselves, it’s hard to build something when you haven’t had money, ever. And now everything costs money. But from the very beginning, [it’s been] explicitly about descendants of chattel slaves.

I see people encompassing the non-monetary more frequently or in a more nuanced way now. There is the UN definition of reparations – the guarantee of non-recurrence, formal apology, money – the UN has multiple pillars on the official definition of reparations that’s international.

I want laws changed. I want an actual, small “d” democratic republic that’s a representative democracy… and more in the line of equity rather than equality. A lot of life changes for the Black population have centered around access and resources, which yes, leads you towards equality. That doesn’t necessarily bring you further to equity – it gets you closer, but there’s still a long way to go between equality and equity.

Those are the parts I feel my colleague and I also focus on. I think a lot of that comes out of how I was raised in politics.

We look at the root word: we’re talking the word “repair”. Finance isn’t the only way. Money isn’t the only way society needs to be repaired. People’s minds, socially, need to be repaired and retooled; entire systems do, even just the way people understand institutions needs to.

We’re looking at what is broken – which is everything, essentially – but we really look at the root of the word, even down to family. Not in that sense of being like, “My family is broken”, but the broken understanding of your family and your ancestors and how they did/didn’t shape and contribute to American society and the way it is today.

Emma:

Could you tell us a little bit about genealogical reparations – what they are exactly, and why they’re so important?

…there’s a lot lived in the dash in between, but [death is] the next time you really get cohesive information about the person and where they come from and who they come from. So really working with people to insert their ancestors into history.

Briayna:

Yeah! So, a slight background: that came about because my counterpart and I realized that we were connected in a way after multiple years of working with each other. She, in looking back, was like, “Oh, looks like I have some ancestors from Maryland. Have you heard of *this* surname?”

And I’m like, “…The original colonizers of my state? What do you mean? <Laugh> Of course I know who that is! Have you seen our state flag? Do you know what street I work on? The name of my building that I work in? I know exactly who they are.” Even other surnames that pop up in southern Anne Arundel County and Virginia are still in the area.

So in doing what we’ve coined as “reparative genealogy”, we focus on working with people – white and Black, and then some people have been mixed, teasing out what that looks for them as well – looking at and understanding history through the lens of your ancestors.

So whether that starts in 1917 with your family immigrating here and immediately learning, “Oh, we need to assimilate into whiteness, ’cause what we don’t wanna do is be treated like these Black people”; whether it’s that, or going back to people who were some of the first settlers here… [for example] one of Lotte’s ancestors was an explicit part of Native removal and receiving land grants and being requested to clear Natives off of land and open it up for settlers.

So teasing that out to really understand… for some people, what they may have heard about, read about, and, if we’re real lucky, learned about somewhat in school; but on the whole people that have no clue [of] the ways in which our country was created and white supremacy was created and exacerbated, and pinpointing how their ancestors were a part of that; or if they’re Black, or just non-white, how their ancestors were affected by that or not (but on the whole are).

[Also] working with people to really understand how to look at birth and death certificates. As you go further back in time, the cursive and script gets much more particular. The scientific terms for things like heart attacks and whatnot are completely different. So, even just understanding terminology…

Places to look for those kinds of documents: people know about birth and death certificates and the census records, but mention a probate record or a plat record, and they go, “Hold on, what is that?” Or, you know, a city directory; and it’s like, “Oh, they listed people in there, not just businesses? It was basically the yellow pages!” So teasing out even some of the other options there.

I am the grim person when it comes to paperwork, where I’m like, “Let’s talk about the information you can get, in particular for Black folks, from obituaries.”

That’s really when people come together to piece together people’s lives outside of when they’re born. Of course there’s a lot lived in the dash in between, but [death is] the next time you really get cohesive information about the person and where they come from and who they come from. So really working with people to insert their ancestors into history.

A lot of people, when they learn history, it’s abstract or something where you learn about it in a very detached way, unless there’s something that just really captures your interest and you’re like, “Oh, I wanna follow this all the way through. I wanna go down all the rabbit holes. This is my new thing to obsess over.” People like myself in that way are very few and far between, but genealogy is a way for people to get into that.

People may do a family tree, but you get to a point [where] you know they’re a 24-year-old woman in Mechanicsville, Virginia in 1780. You’ve got a name, you’ve got a date, you’ve got a place… okay, but what was there to do in society in 1780… as a woman?

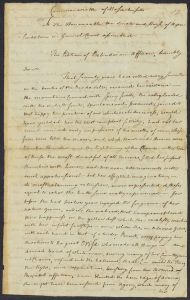

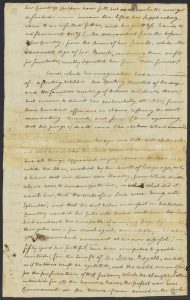

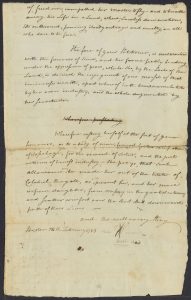

A petition for reparations by Belinda Sutton on February 14, 1783. Belinda was formerly enslaved by the Royall family. After several petitions to Massachusetts, she was given reparations in the form of a pension from Royall’s estate. Credit: Harvard Library.

What could she have been doing? What would she have had access to? What was her husband doing (’cause a lot of what she’s able to do or not do is related to her husband)? What does she have to be okay with going on in her household? Just those kinds of questions to really put meat on the bones and names of people, and getting people to come to history and to reparations in that way.

The way that we get people on board with reparations isn’t even explicitly trying to hammer it over their head. It is, “Okay, let’s talk about some stuff. You may have heard about it, you may have not. But we’re gonna talk about it, and we’re gonna use our family to tease it out and give you examples.”

By the end of it, people will go, “Oh… Now hold on… And you said there’s this thing called reparations? Give me a minute… What you said makes sense, but I’m very scared. I was scared by this reparations word, but maybe I’m less scared. Let me get it together.” They come to it themselves, which I don’t know that we ever anticipated happening.

Now whether or not they’re still willing to have their tax dollars funding it or whatever the case may be is a whole other thing, but they at least understand the logic of it.

Emma:

Yeah, that makes total sense. I love what you said about putting meat on the bones of different ancestors’ history. Just touching on that SURJ event [last year] – you mentioned something specifically about why that process is so important, particularly because of the history of the abduction and enslavement of the Black community here. Could you go into why that is so important, that genealogical discovery and mapping?

Briayna:

The first thing I’ll say is, it’s important because it’s hard and the difficulty is usually the deterrent for some people. But that, for me, makes it all the more important.

At this juncture, at this point in society, it’s extra important – especially when you’re talking oral histories and looking at old documents – because we still have people that lived through some of the most prominent civil rights changes in the last few centuries.

When you think about the end of enslavement, marking emancipation, you’re going forward another hundred years before massive changes happen again. You’ve got people living today that can take you back to the 1800s, just with the people they grew up with.

When you think about the longest living survivor of the Tulsa massacre, who’s still of sound mind enough to have published a book last year… In missing our chance to record and collect that, and gain a sense of self from their stories, their experiences… It’s something we can’t really recreate later if we don’t get it now.

For me, it’s always been a big part of my sense of self. I grew up with our community historian, and she was also our family genealogist. You were not going to spend any significant amount of time with her and come out of it not knowing who your ancestors were or where we came from, or who our people were at least back to when we moved to the town…

My family members have been part of a lot of the pivotal things in our area. [I want] to make sure that is documented and remembered, while giving people their flowers while they’re living.

Our generation and younger, we are at such a great time to be alive, so to speak, despite the hellscape that is life <laugh>. But the access to technology, the technological equipment that we have, the Elders that are still living and that have sound mind, that combination is unprecedented, honestly.

Being able to just pop up at my grandfather’s house and hit a button on my iPhone and sit and be like, “Hey, I’ve got this question about when you integrated the police department,” and have his voice and get all of his intonations and be able to take notes from that and transform it into other things, is not something my mom really had access to…

This is a time that is, to me, not like any other and not like there will be – the closeness of the people to [those] who were sharecroppers; or, depending on the age, enslaved.

When you think about the longest living survivor of the Tulsa massacre, who’s still of sound mind enough to have published a book last year… In missing our chance to record and collect that, and gain a sense of self from their stories, their experiences… It’s something we can’t really recreate later if we don’t get it now. That aspect deepened for me a few years ago before I was really in the thick of genealogy…

I always knew that my mom grew up in the house with my grandfather’s grandfather, but to say in a full sentence… My mom, who really is not that old, grew up in a house with a man born in 1885. It continues to, and probably will always, blow my mind.

And it’s not like, “Oh, well, you know, and then he passed when she barely had a memory.” No, she lived with that man, and he lived in that house until she was a teenager. She was halfway done high school. So she started really coming into herself and was raised by a man born in 1885 who had the equivalent of a fourth grade education.

She’s not alone in that. So many people grew up with not only their grandparents, but great-grandparents in the home, or in and out of the home, or spending time at their houses.

They come from much more pivotal points in history and time than you or I to have our grandkids grow up in the same house with us. The most throwback stuff I can tell them about is VCRs and Walkman’s and using an encyclopedia and almanac to do my homework. Not, you know, “My parents were sharecroppers,” or they were the first in our family to be free.

“I remember when I couldn’t get a loan for my house. I had to build it myself, which meant I had to learn how to build one myself because I was a waterman; I wasn’t really a carpenter.” Like nowhere near the same.

Emma:

That’s amazing about your mom and her grandfather, it’s a trip to think about how close history can be. Who is your family genealogist? Who’s the one who passed that on to you?

Briayna:

Her name was Marita Carroll. She was a cousin of ours. She passed 10 years ago last year. She was a part of the Annapolis Five who were one of the pivotal events for integrating restaurants here.

She also did a lot with the politicians, a lot of them that have recently (finally) gotten out of office in the last few years. A lot of our legislators at the city, county, state and federal level, she helped to get into office and fine-tuned their political stances. And orchestrated a lot of the civil rights initiatives that happened here in our area. That was her.

She integrated my elementary school as the teacher. My aunt and some of the other kids integrated as the students, but they literally handpicked her from another school in South [Anne Arundel] County and asked her to come back home and integrate their school up here. She was at South County, she moved to teach at Parole, and they asked her on a Thursday at Parole if she would integrate and be the Black teacher at Eastport. And she was like, “I mean, sure, I’m from there. That’s fine.”

“Great. Can you do that Monday?”

She finished teaching at Parole that Friday and started teaching at Eastport that Monday.

Emma:

Wow. That’s brave. That’s a lot of change so quickly.

Briayna:

They knew of her, the respect that the people in the community had for her and for our family. So they’re like, “All right, we know the caliber of person we’re working with. If it’s her, we be alright! Good teachers and stuff will follow, and we just won’t have to worry about doing stuff for these Black kids. She can do the rest.”

Emma:

Well, I’m happy that [the children] had such a powerful resource… to help them. Is it with that family historian that your personal journey with reparations work began, or when did that start?

Briayna:

No, mine started in 2018, honestly, when Lotte and I started working together.

I’ve known about the concept of reparation since I was a kid growing up with [Marita]. She was also the one that taught me about sharecropping – not necessarily calling it the term that I use, which is slavery 2.0, but… that’s what I understood it to be at that time, and it’s still applicable.

Those are the concepts that I learned from her as a kid, which gives insight into the type of person she was: an old woman willing to have that conversation with an elementary school child.

It started five years ago – I went to a conference in Virginia and reparations was the topic of one of the workshops. And I was like, “…what do white people know about reparations? Let me be in this. Let me sit in this here circle.”

As I listened to people, in my understanding of it and understanding politics and the intersection of race and politics for me, just with how my brain works, immediately was like, “Okay… so money is great, but there’s a whole lot of other things I need from y’all. Civic engagement for one, but a very particular type of civic engagement. I can’t have y’all supporting conservative laws… That’s not what I need from you when I say civic engagement.”

That was where it started, because even after I said my piece in that workshop I had people come up to me after where they’re like, “I just hadn’t thought about it that way.”

It’s a case by case basis: what do people need? Why are they in the circumstance they’re in? Knowing your genealogy, for me, is a big part of that.

When you talk about education, for example – I do come from some teachers, but I was a first generation college attendee and graduate on my dad’s side.

Then on my mom’s side, my grandmother was the only one out of 17 children to go to and finish high school, and go to and finish college. That’s just my grandmother! A lot of that had to do with lack of access; then, you know, almost all of the kids having to work a tobacco farm that used to be the tobacco plantation they were on…

I can point the direct lines. So when people want to refute logic, so to speak, I’m like, “Okay, well then here’s the personal angle. Let me tease this out for you and how it brings us to present day: my current circumstances, my cousins’, my mom’s, all of them.”

I don’t think I foresaw it being what it’s come to today. Now we’re in a documentary that has another premier this evening and all that, I definitely did not see that coming. I just wanted people to stop being under- and misinformed and, outside of those two categories, willfully ignorant.

Emma:

I saw that there’s a documentary on your website. Congratulations!

Briayna:

Thanks! …They’re trying to get me better about marketing, and I just, I have a lot going on. So for me to also do that and then have people also make inquiries about that, I don’t have time for <laugh>…

Check back for PART 2 at the end of February!